Fifty Years of Assessing Worst Case Needs for Affordable Rental Housing

Barry L. Steffen, Social Science Analyst, Policy Development Division, PD&R (1995-present)

The rising prevalence of worst case needs among very low-income renters reflects the increasing dominance of housing cost burden rather than housing inadequacy as a cause.

Among the research that the Office of Policy Development and Research (PD&R) produces, one of the most high-profile products is the series of Worst Case Housing Needs reports to Congress. These reports, which span most of PD&R's 50-year history, have supplied researchers and policymakers with critical data and insights about needs for affordable rental housing in the United States. For decades, a household with "worst case needs" has been defined as a very low-income renter household (earning less than 50 percent of the area median income) who lacks housing assistance and also has a severe housing cost burden (housing expenses that exceed half of the household's income), a housing unit with severe physical inadequacies, or both.

The prevalence of worst case needs has increased markedly over time. As the U.S. population expanded between 1978 and 2021, the nation's very low-income renters increased by nearly 81 percent, from 10.7 million to 19.3 million—but HUD's estimate of households experiencing worst case needs increased 115 percent, from 4.0 million to 8.5 million, based on the most recent report (Alvarez and Steffen 2023).

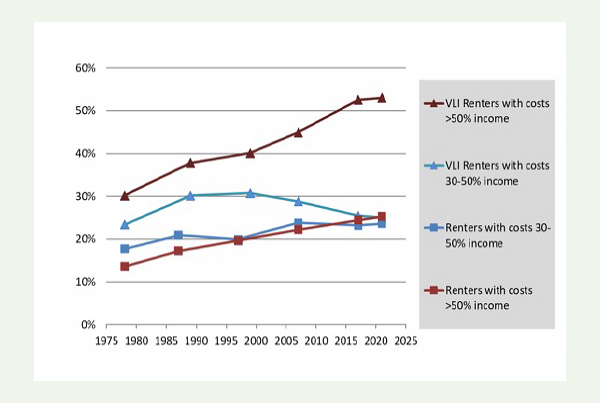

The rising prevalence of worst case needs among very low-income renters reflects the increasing dominance of housing cost burden rather than housing inadequacy as a cause. The percentage of very low-income renters with severely inadequate housing was 9.0 percent in 1978, decreasing to 3.4 percent in 2021. The share of very low-income renters experiencing severe cost burdens has had the opposite trajectory, increasing from 30 percent in 1978 to 52.9 percent in 2021 (exhibit 1). The percentage of very low-income renters with moderate cost burdens of 30 to 50 percent of income increased during the 1990s but then began falling, and since 2000, the percentage of renters experiencing severe cost burdens has eclipsed the percentage of renters experiencing moderate cost burdens.

Exhibit 1. Prevalence of Severe and Moderate Housing Cost Burdens Among All Renters and Very Low-Income Renters, 1978–2021

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey

These data suggest that from their start, HUD's Worst Case Housing Needs reports have targeted a serious and growing challenge. How did this emphasis come about?

Origin of Worst Case Needs Reporting

PD&R published the first of its regular Worst Case Housing Needs reports in response to a 1990 report from the Senate Committee on Appropriations that accompanied HUD's fiscal year 1991 Appropriations Act. In it, the committee directed HUD to

resume the annual compilation of a worst case housing needs survey of the United States... [to estimate] the number of families and individuals whose incomes fall 50 percent below an area's median income, who either pay 50 percent or more of their monthly income for rent, or who live in substandard housing.

To estimate unmet needs for additional assisted rental housing to serve eligible households, PD&R provided the Appropriations Committee (and perhaps other committees) with multiple estimates of worst case needs during the late 1980s. The committee's directive established several notable priorities:

- It clarified the reports' emphasis on renter households.

- It maintained a focus on very low-income households rather than low-income households eligible for housing assistance.

- It maintained a focus on households experiencing severe housing cost burdens rather than those experiencing moderate housing cost burdens. The lower, moderate-burden standard might align better with the 30 percent of income that assisted tenants were required to contribute toward rent after Congress' 1981 tweak of the original 25 percent standard outlined in the Brooke Amendment (Eggers and Moumen 2008), but the lower standard would have included households with a marginal financial need.

- It redefined the worst case needs standard to include individuals in addition to the families prioritized for HUD's housing programs—that is, both families with children and those with a head or spouse of 62 years or more, classified as "elderly."

The first published Worst Case Housing Needs report reported a total of 5.1 million very low-income renters with worst case needs in 1989, which it divided into 3.6 million family and elderly renters classified as having "priority problems" for program purposes and 1.4 million renter households who had the same type of severe housing problems but were composed of nonelderly, unrelated individuals (HUD-PD&R 1991). The growth of severe cost burdens among very low-income renters illustrated in exhibit 1 underscores the wisdom of the committee's priorities.

The prominent role of the Appropriations Committee highlights the importance of the worst case needs measure in the policymaking process. As the 1991 PD&R report describes it, the 1980s-era estimates were intended to support a "model projecting how combinations of turnover [of assisted units] and incremental units could meet worst case needs." Gordon Cavanaugh (1992) provides a similar context:

The…worst case motif was originated in 1984 or 1985 by Wally Berger, a wise Senate appropriations staffer, as a means of getting the national Administration to commit to a higher and more predictable level of funding than was otherwise likely. At the time, HUD assured Berger's HUD and Independent Agencies Subcommittee that an annual incremental level of 100,000 units, the worst cases would be eliminated within six to seven years….[H]ow wide of the mark that forecast was….

Technical Basis for Worst Case Needs Measurement

The Worst Case Housing Needs reports are made possible by PD&R's sponsorship of the American Housing Survey (AHS). Conducted biennially since 1985, AHS (and its 1973–1981 predecessor, the Annual Housing Survey) is the nation's premier source of detailed data about housing units and their characteristics, financing, and occupants. This wide scope and detailed coverage allow AHS to support worst case needs tabulations of both the financial and physical housing problems that may affect lower-income households.

The use of the very low-income standard to classify households is both a strength and a limitation of the worst case needs methodology. The guidelines for very low-income households—earning less than 50 percent of the area median income—are well aligned with admission preferences for major rental assistance programs, including a new extremely low-income standard (earning less than 30 percent of area median income) established by the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act of 1998. Identifying a very low-income or extremely low-income renter household requires the use of the HUD Area Median Family Income (HAMFI), which recognizes that additional family members require more income to support larger units with higher rents. Unlike a national standard, such as the federal poverty threshold, the very low-income standard, with its family size adjustment, allows household income levels and rent levels to be compared for appropriately sized units within appropriate geographic areas. A disadvantage of the very low-income standard, however, is that researchers have only restricted access to survey data linked with HAMFI because of privacy concerns arising from the geographic specificity of HAMFI.

Extremely low-income households constitute most (63.7 percent in 2021) of the very low-income households who have worst case needs, because affordable housing is even more scarce for those with such financial constraints. Because addressing the acute needs of this income group is so important, Congress' 2014 move to raise the extremely low-income limit to the greater of 30 percent of HAMFI or the federal poverty level, but not exceeding the very low-income standard, was a significant action. This policy makes housing programs available more equitably in lower-income areas and has not notably shifted the extremely low-income share for worst case needs analysis since 2015.

The concept of worst case needs for housing assistance logically excludes households that already have such assistance. Using a survey such as AHS to determine assistance status, however, is a complex endeavor. The use of a single direct question has proven quite unreliable, yielding both false positive and false negative responses (Gordon et al. 2005). Refinements to the AHS instrument over the years have resulted in estimates of the assisted population that are close to HUD's administrative tallies; it remains difficult, however, to be confident that a household that AHS classifies as assisted is benefiting from a federal program rather than a state or local program. Although HUD and the U.S. Census Bureau are able to match AHS respondent addresses with tenant addresses in administrative records, some tenant addresses remain incomplete and HUD continues to use self-reported assistance status for estimating worst case needs.

Role of the Office of Policy Development and Research

PD&R's administration of the AHS and its estimates of program income limits are central, functional strengths supporting the analysis of worst case needs. The strong analytic skills of PD&R staff also helped the office generate worst case needs reports in house.

Kathryn Nelson was a PD&R research economist who was instrumental in shaping the content of Worst Case Housing Needs reports back when analyzing AHS data involved coding with Fortran and submitting batch runs on the mainframe computer and storage tapes. Another key contributor over the years was David Vandenbroucke, a PD&R economist who assumed much of the responsibility for working with the U.S. Census Bureau to coordinate the design and administration of the AHS.

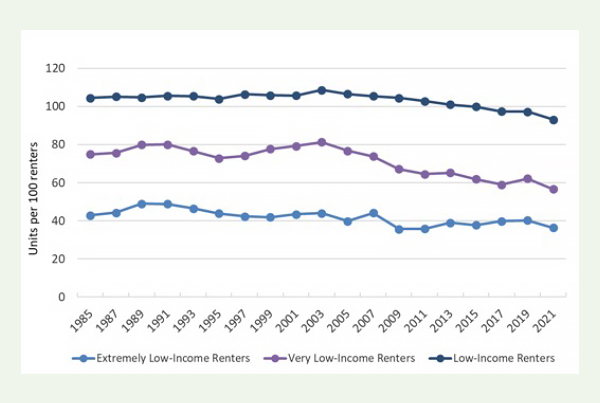

Vandenbroucke (2007) made a major contribution to the Worst Case Housing Needs reports by developing housing mismatch measures. These indicators provide essential insights into whether affordable housing supply (including both naturally affordable and rent-assisted units) is sufficient by comparing the number of rental housing units affordable to households at various income levels with the number of renter households earning those incomes.

Three increasingly stringent mismatch metrics involve the basic Affordable ratio; the Affordable and Available ratio; and the Affordable, Available, and Adequate ratio. The availability criterion recognizes that the existence of a potentially affordable unit cannot itself prevent housing cost burden for a very low-income household if a higher-income household that could afford a more expensive unit occupies that unit instead. Approximately 35 percent of the housing stock that would be affordable to very low-income renters is unavailable to them because higher-income households are renting those units. Likewise, the adequacy criterion is particularly important for quantifying housing problems for extremely low-income renters. The scarce units affordable and available at such incomes are likely to be obsolete, poorly maintained, or suitable to be condemned.

The lowest line in exhibit 2 shows that for extremely low-income renters, the sufficiency of the affordable and available housing stock has nearly returned to the record-low levels experienced after the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. For very low- and low-income renters, sufficiency is reaching new record lows.

Exhibit 2. Sufficiency of Affordable and Available Rental Units, by Relative Income, 1985–2021

Source: HUD-PD&R tabulations of American Housing Survey.

Interpreting Worst Case Needs

The congressional directive to tabulate worst case needs implicitly asked HUD to quantify the unmet need for rental housing assistance. Indeed, the Senate directive also urged HUD to develop a strategic plan "that outlines how the Federal Government, despite limited fiscal resources, can help to eliminate or substantially reduce the number of families and individuals who fall into this worst case needs category."

In practice, policymakers have found the extent of worst case needs and the cost of housing assistance to be daunting problems. Congress has never sought to scale up federal housing assistance enough to serve as an entitlement for any income-eligible renter with severe housing problems. Therefore, researchers and policymakers should acknowledge that worst case needs is a measure of unmet need for both assisted housing and affordable housing.

The private housing market provides housing free of severe cost burden and severe housing inadequacies to slightly more very low-income renters than do federal rental assistance programs: AHS data for 2021 show that, among very low-income renter households reporting either no housing problems or only nonsevere housing problems, 5.1 million had housing assistance and 5.7 million had no assistance (Alvarez and Steffen 2023). This finding suggests that supporting the production of naturally affordable housing in the private market would strongly complement policies increasing public rental assistance.

At the same time, the growing insufficiency of affordable and available rental housing, along with the significant increase in the prevalence of severe cost burdens among very low-income renters, accounts for the new record total of 8.5 million worst case needs in 2021. The number of very low-income households with severe problems far exceeds the number of households either receiving housing assistance or residing in naturally affordable private housing. For this reason, the measurement and reporting of worst case needs remains relevant and the necessity for a robust, comprehensive policy response never greater.

Works Cited

Thyria A. Alvarez and Barry L. Steffen. 2023. “Worst Case Housing Needs: 2023 Report to Congress,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

Frederick J. Eggers and Fouad Moumen. 2008. “Trends in Housing Costs: 1985–2005 and the 30-Percent-of-Income Standard,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

Gordon Cavanaugh. 1992. “Comment on Kathryn P. Nelson and Jill Khadduri’s ‘To whom should limited housing resources be directed?’” Housing Policy Debate 3:1, 67–75.

Erika L. Gordon et al. 2005. “Improving Housing Subsidy Surveys: Data Collection Techniques for Identifying the Housing Subsidy Status of Survey Respondents,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.

Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on HUD and Independent Agencies. 1990. Committee Report to accompany H.R. 5158, The VA-HUD Appropriations Act for FY 1991 (S. Rpt. 101-474).

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. 1991. Priority Housing Problems and “Worst Case” Needs in 1989. https://www.huduser.gov/portal//Publications/pdf/HUD-5828_WorstCase1989_report.pdf.

David A. Vandenbroucke. 2007. “Is There Enough Housing to Go Around?” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research. 9:1, 175–188.

See: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. n.d. “Income Limits: Frequently Asked Questions, Q4. Why is the Extremely Low-Income Limit much higher than in the past and sometimes no different than the Very Low-Income Limit?” Accessed 21 July 2023. ×